Design Solution for Hypothesis 1

Reimagining sustainable educational facilities for students

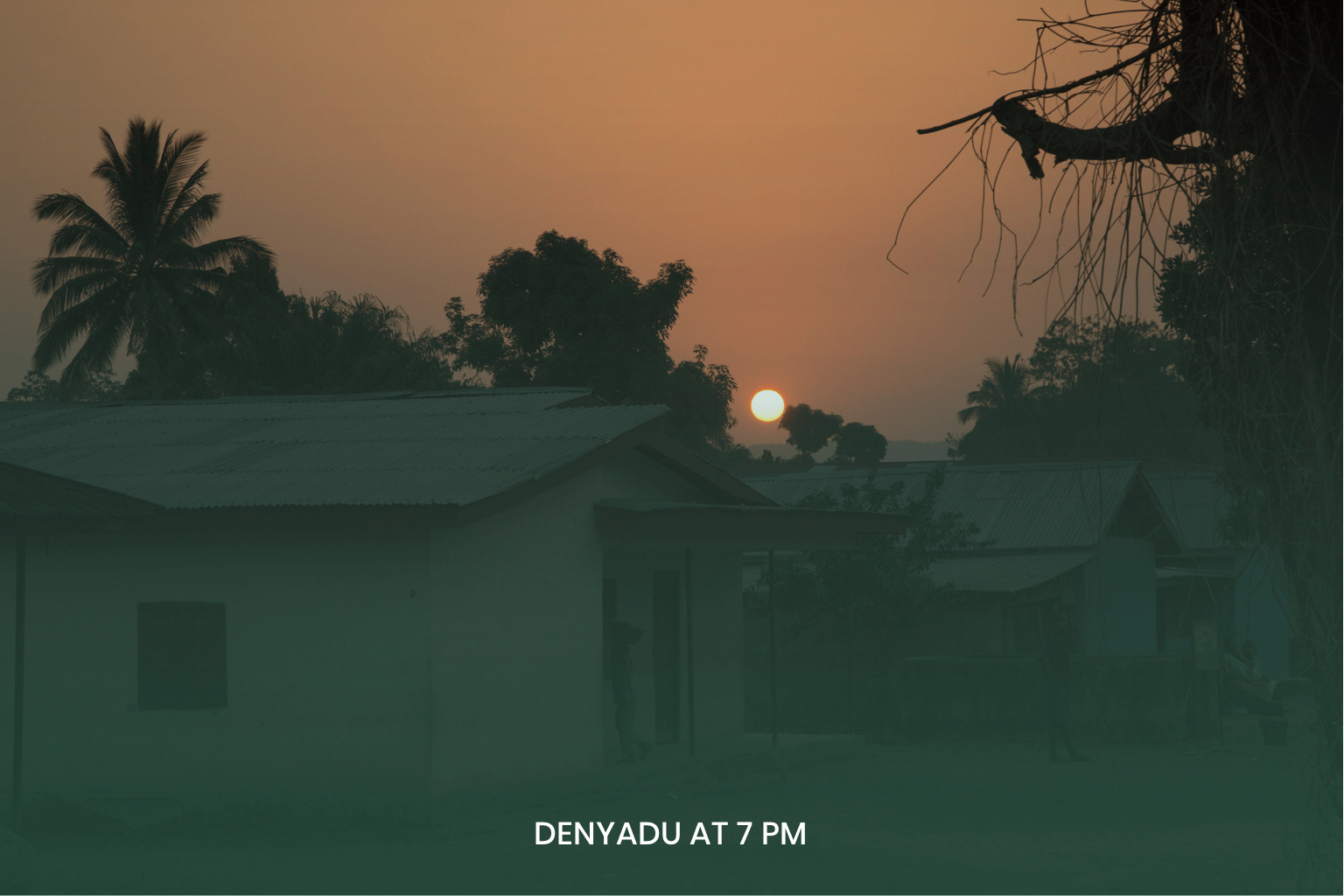

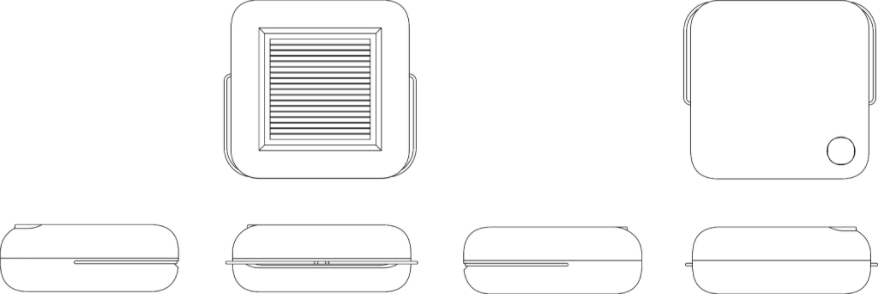

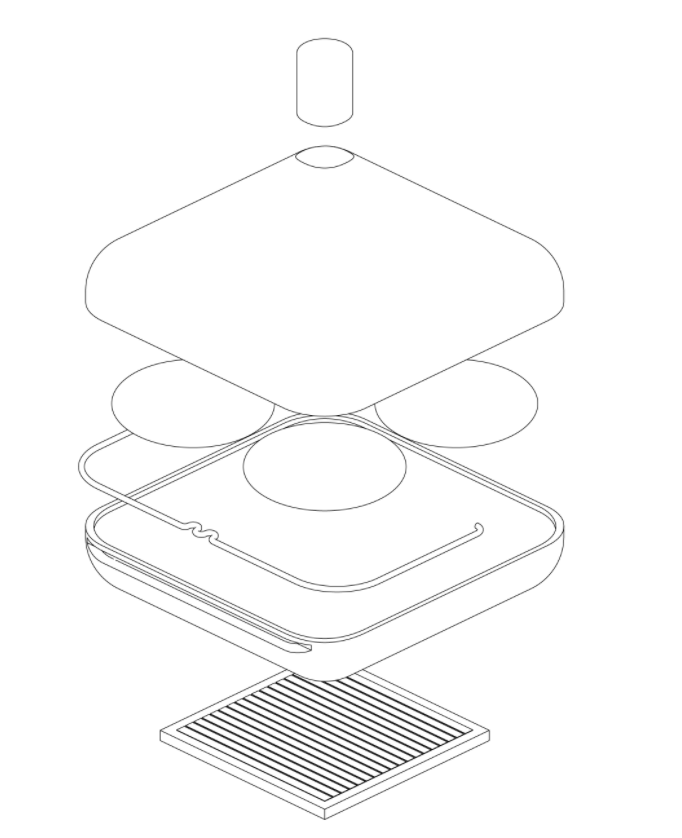

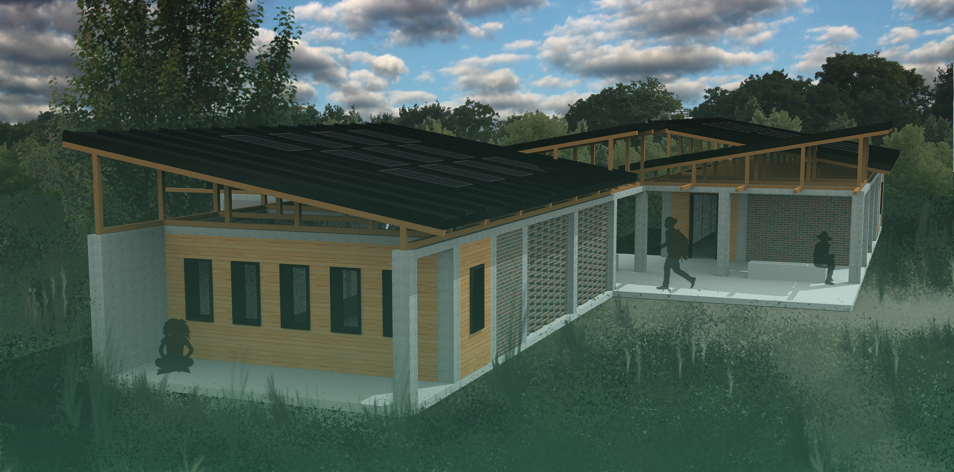

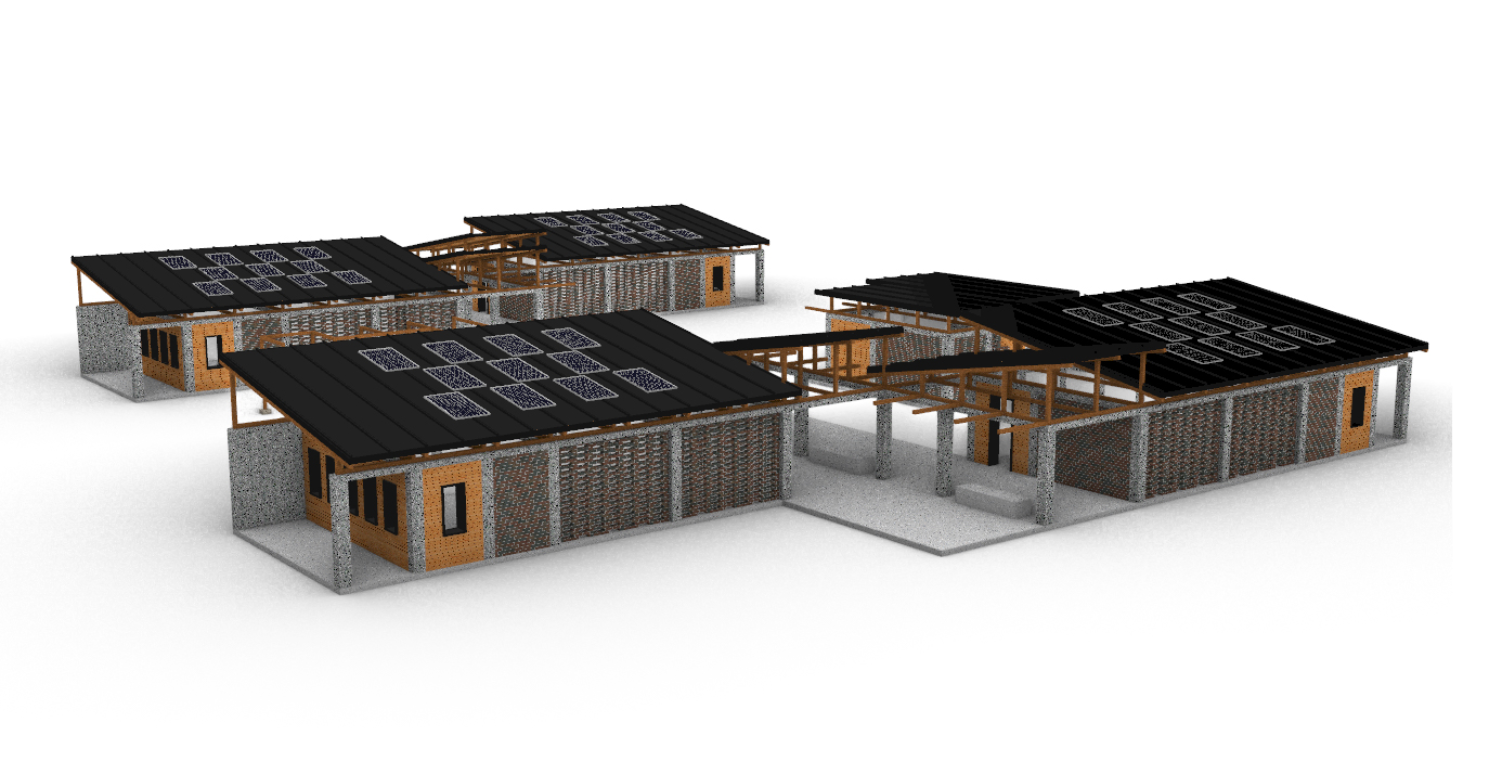

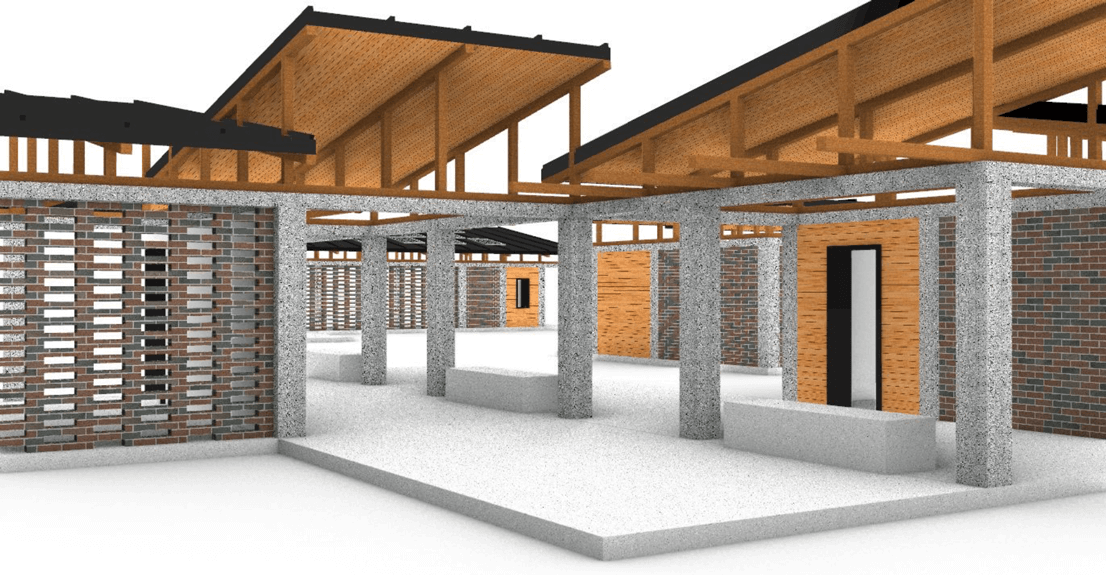

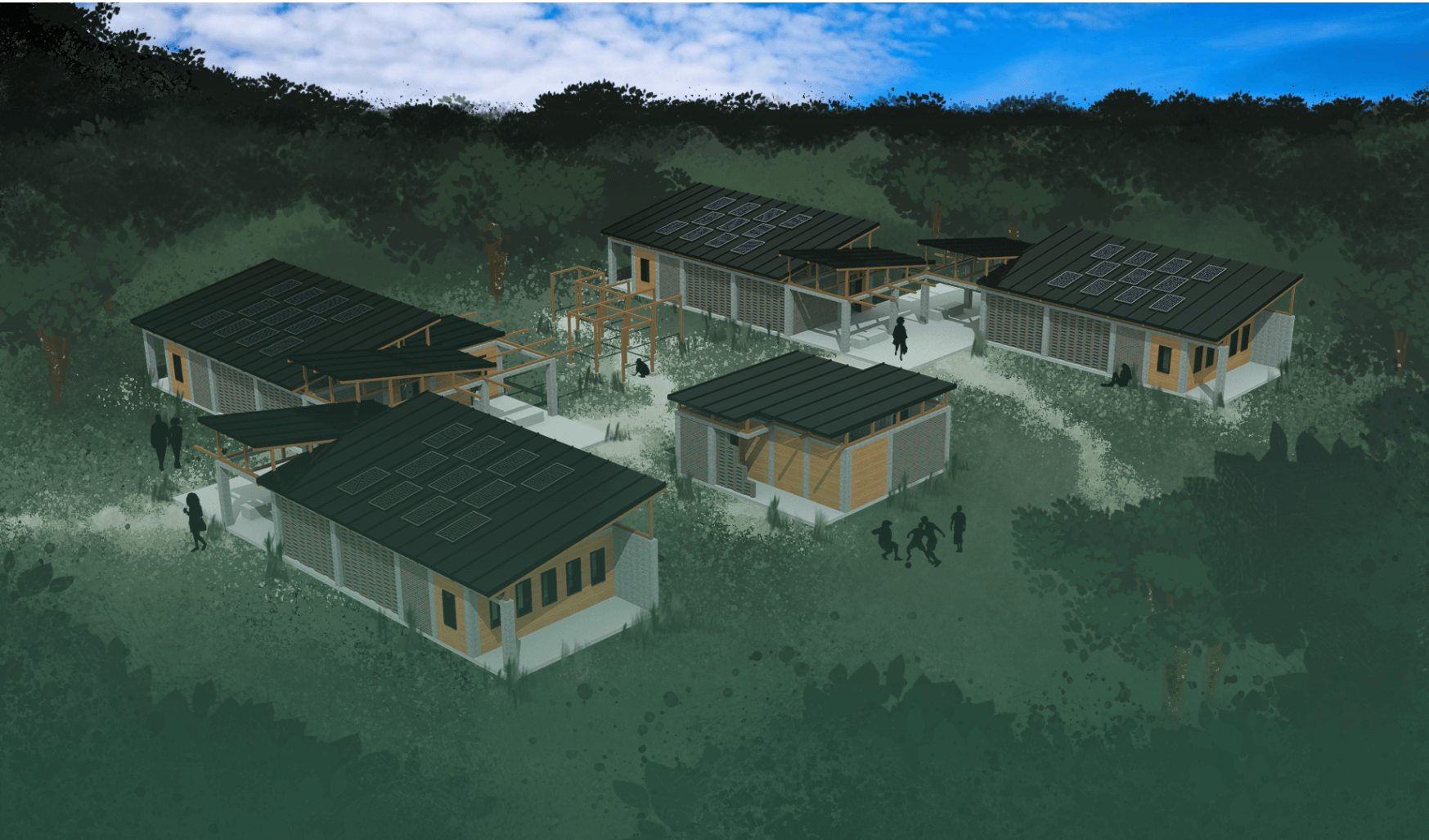

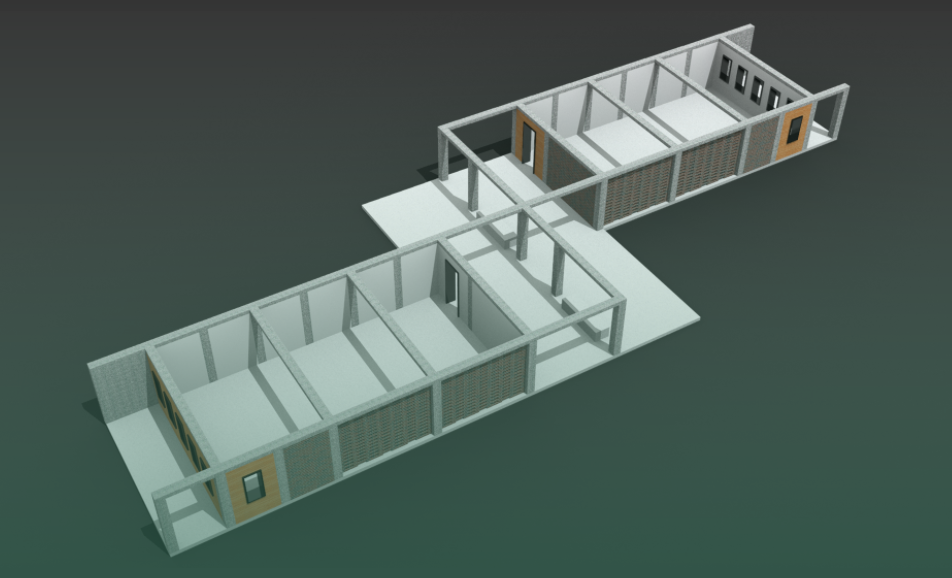

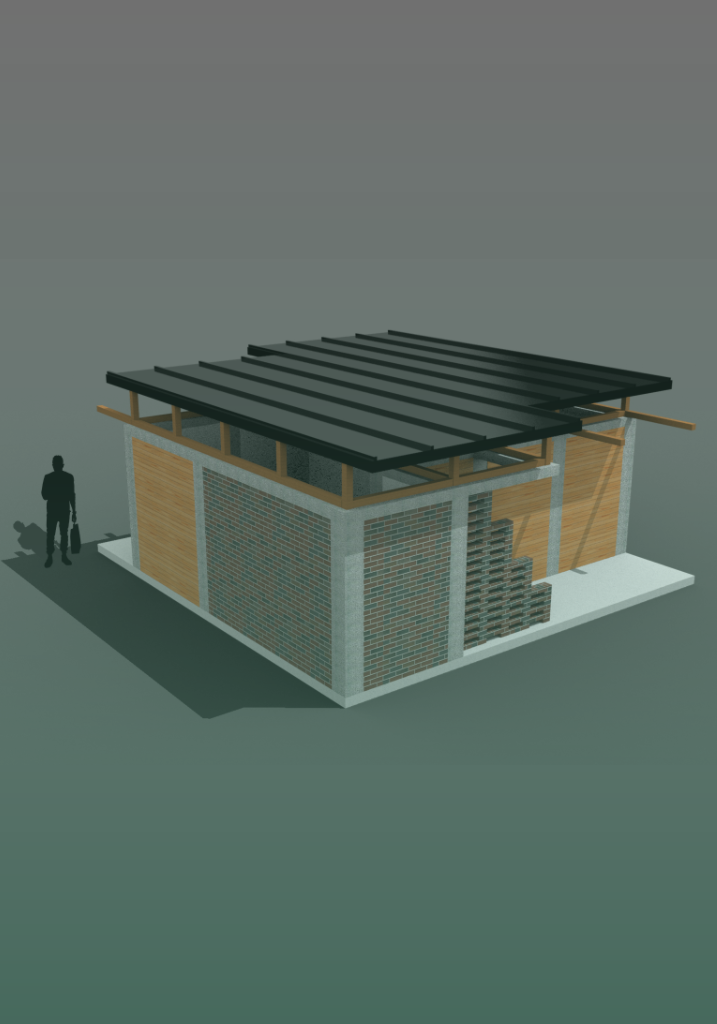

As our prototype for the lantern was being developed, we set sights on one of our biggest tasks yet-- reimagining school facilities in the villages. With much time spent on learning about solar panel technology, we enlisted an architect on our team to help us explore ideas with solar panel technology with regards to buildings. We set a goal to pursue solutions to finish the school building using local, and easily renewable resources in the bamboo and timber economies in Kono, Sierra Leone to build the school. We would also solve the problem of overcrowding in the classrooms.

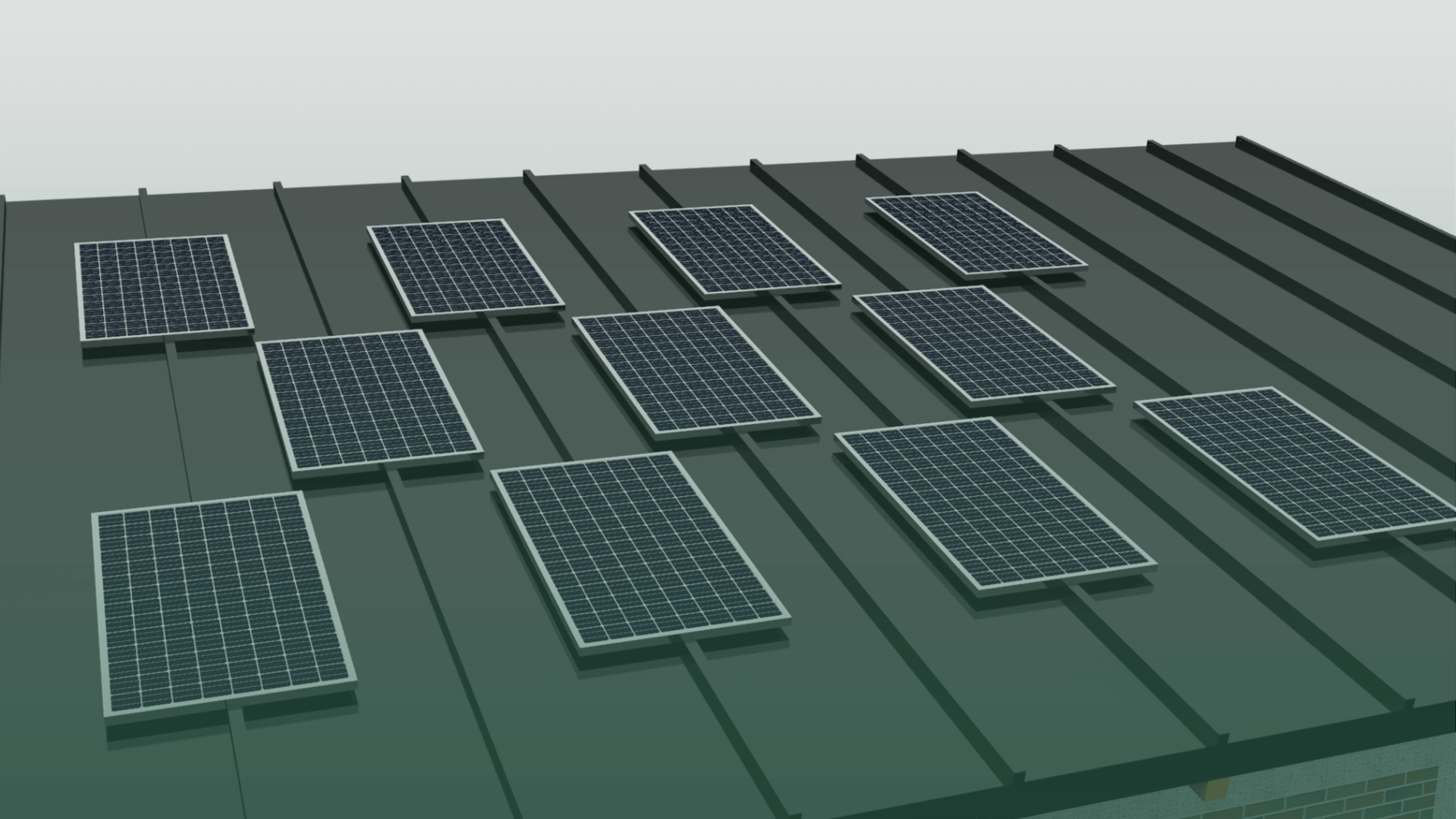

With a month's worth of research, we began creating a net-positive building model, meaning that the school building will produce more electricity than it uses via solar panels. These solar panels will be used to change the lanterns that will be given to members of the surrounding community.