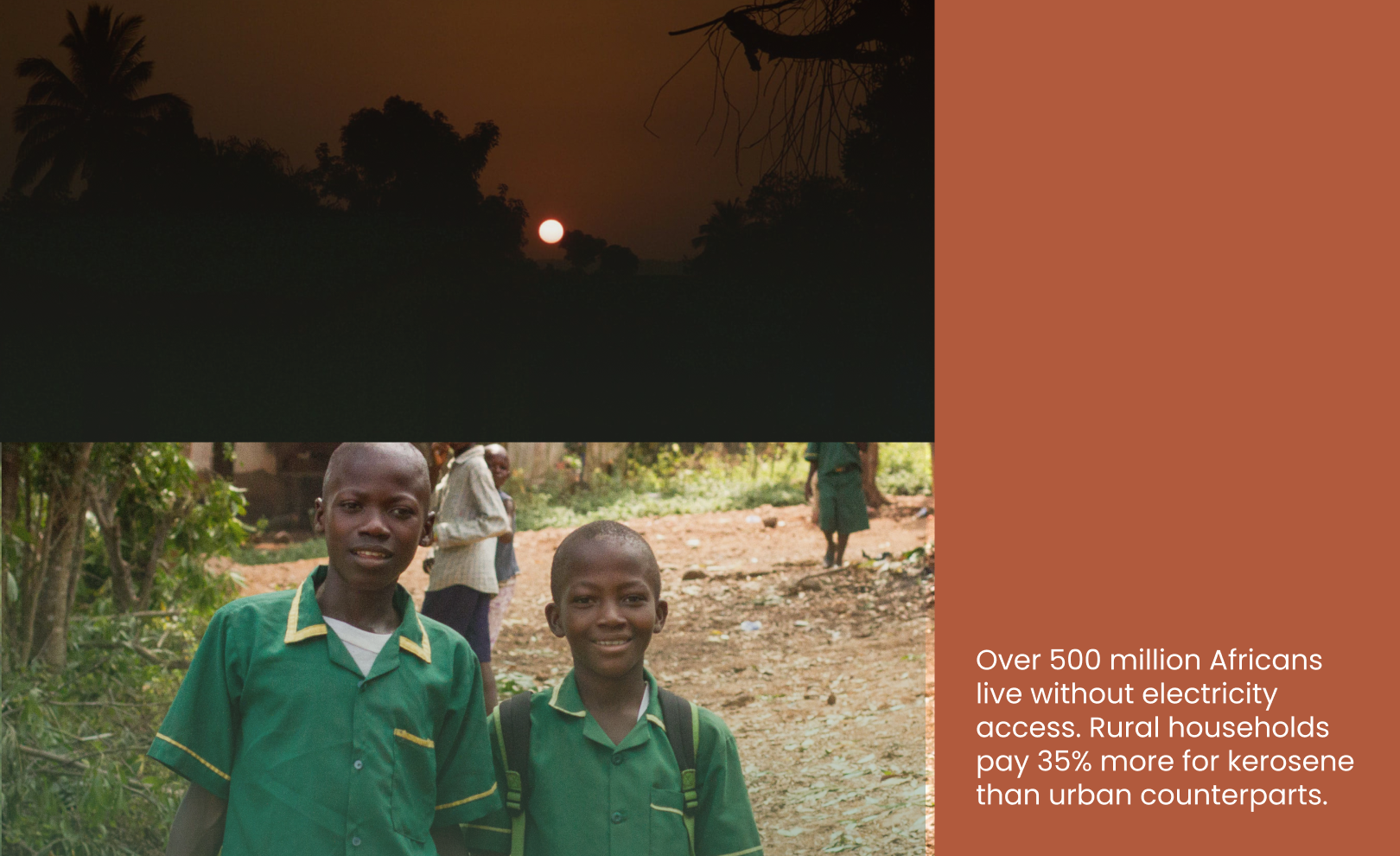

Problem Context

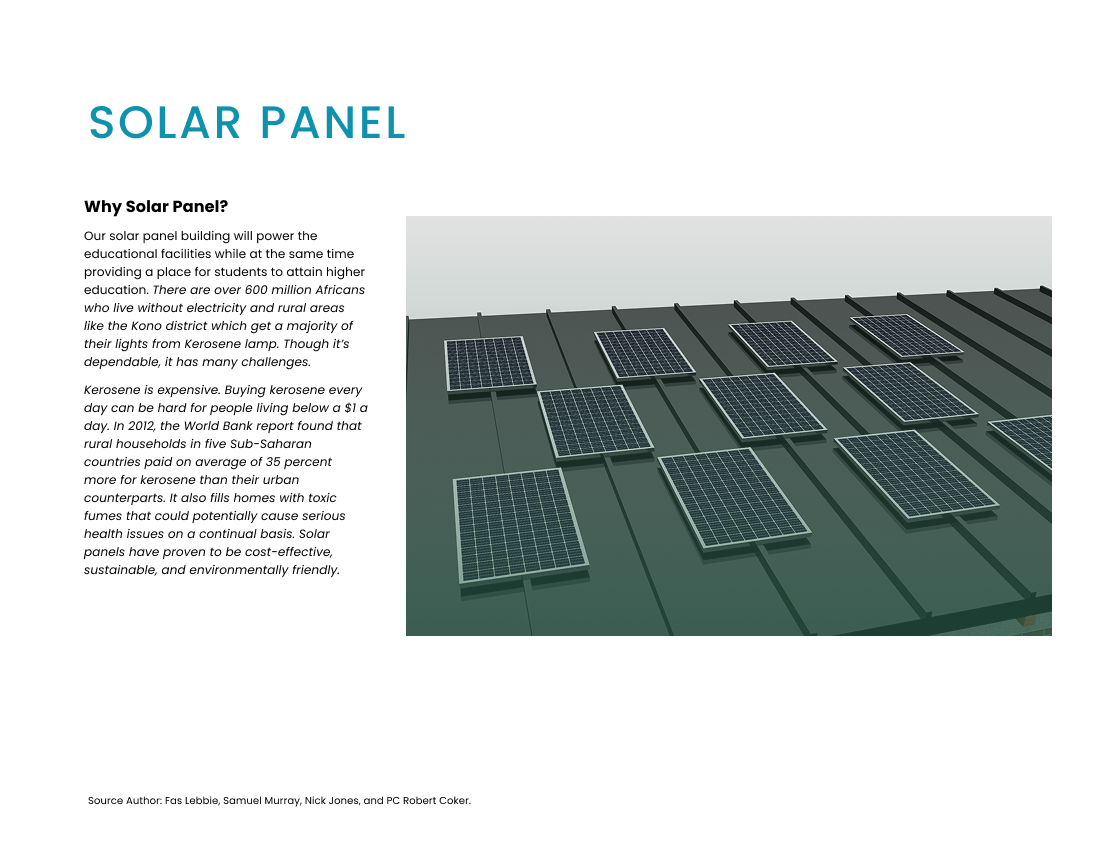

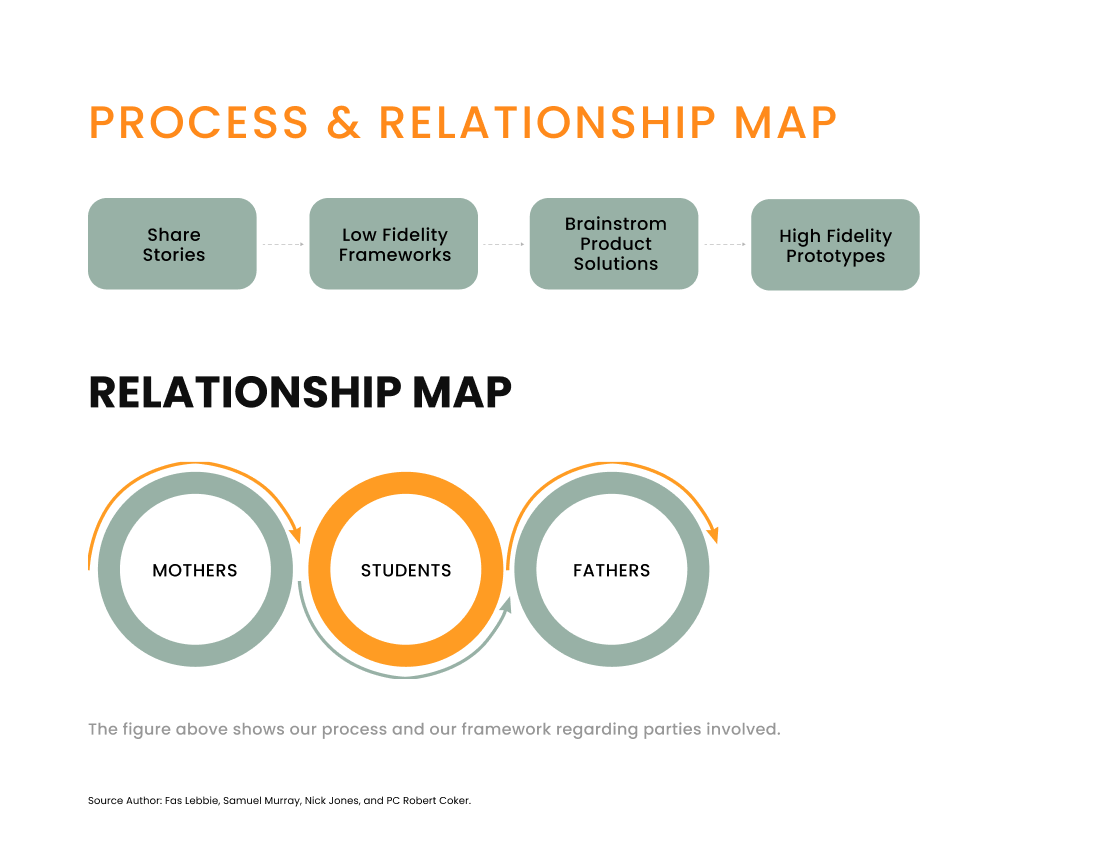

The lack of reliable electricity affects over 600 million people across Africa, with rural communities in Sierra Leone’s Kono District experiencing some of the most severe impacts. When darkness falls around 5 PM, all productive activity effectively ceases—farmers must abandon their crops (leaving them vulnerable to wildlife), students cannot complete homework, and families resort to expensive kerosene lamps that consume up to 35% of household income while filling homes with toxic fumes. These conditions create a cycle of limited productivity, educational disadvantage, and health risks. Traditional infrastructure solutions remain decades away for these communities, yet each day without light represents lost economic opportunity and educational development. The challenge reflects a critical gap between basic infrastructure needs and available resources in regions where most residents live on less than $1.25 daily. This situation presented a unique opportunity to apply human-centered design to create an accessible, sustainable solution that could immediately improve quality of life while respecting local contexts and constraints.