Problem Context

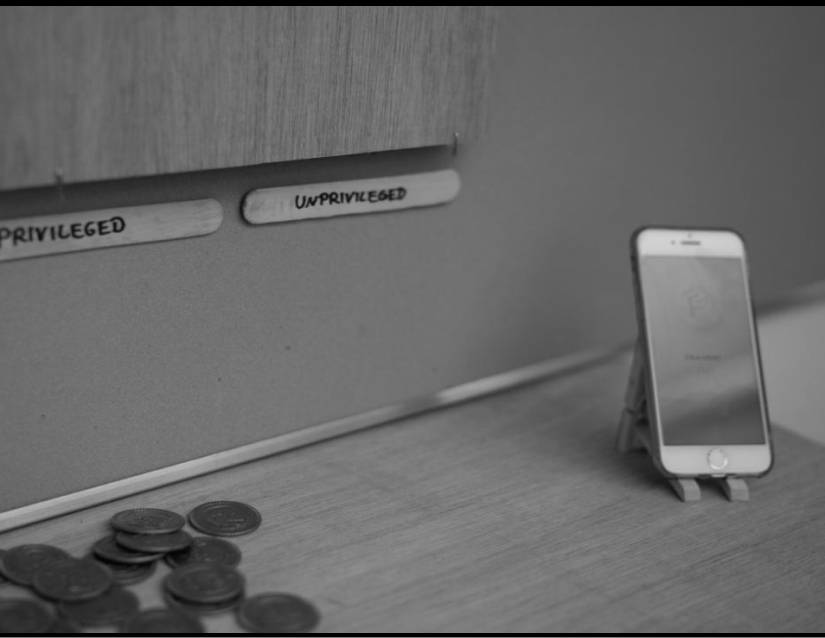

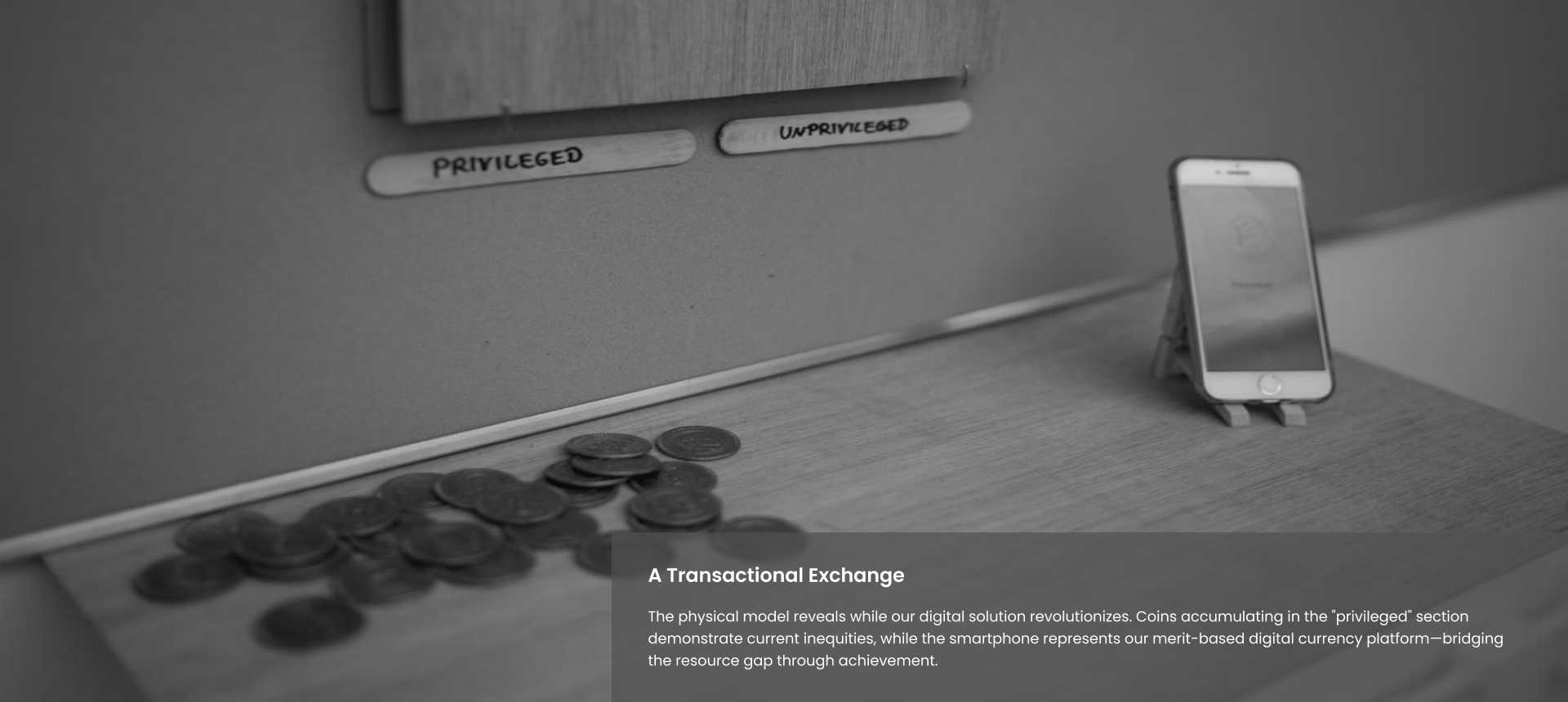

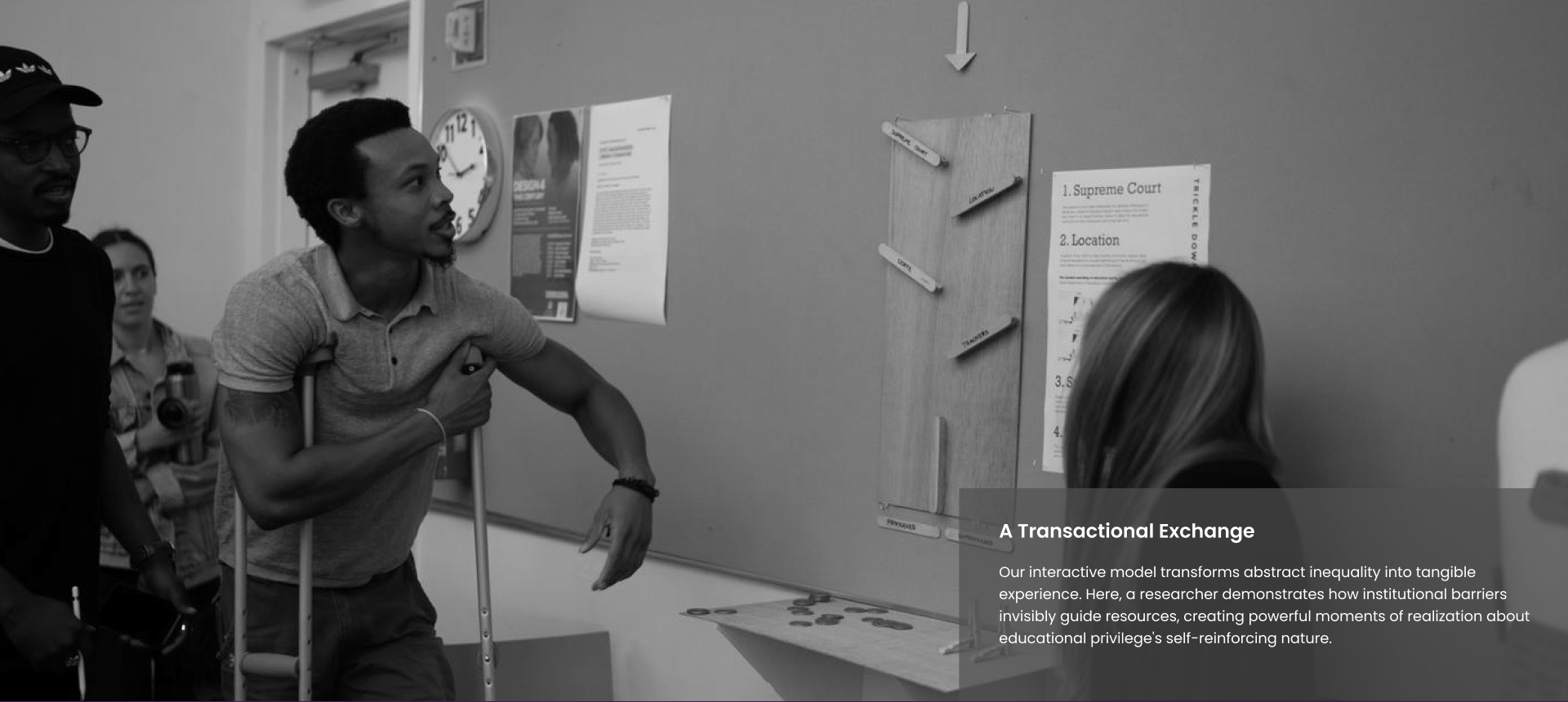

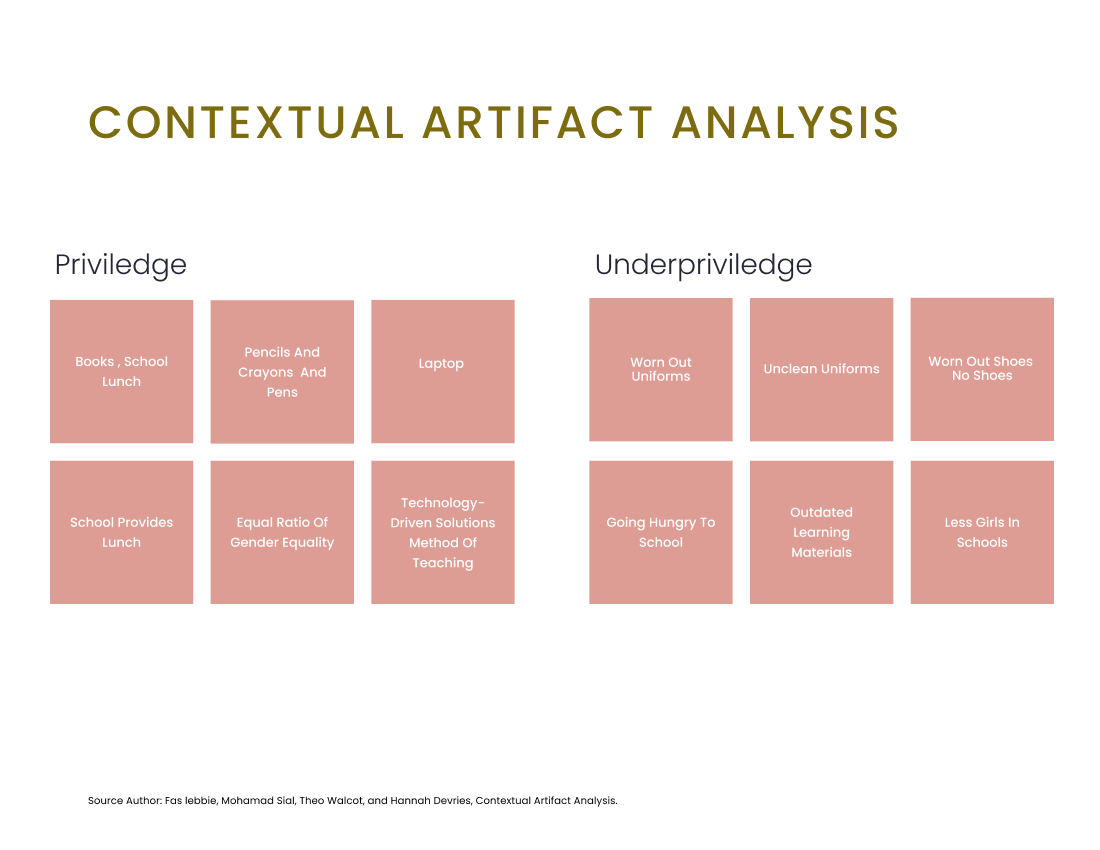

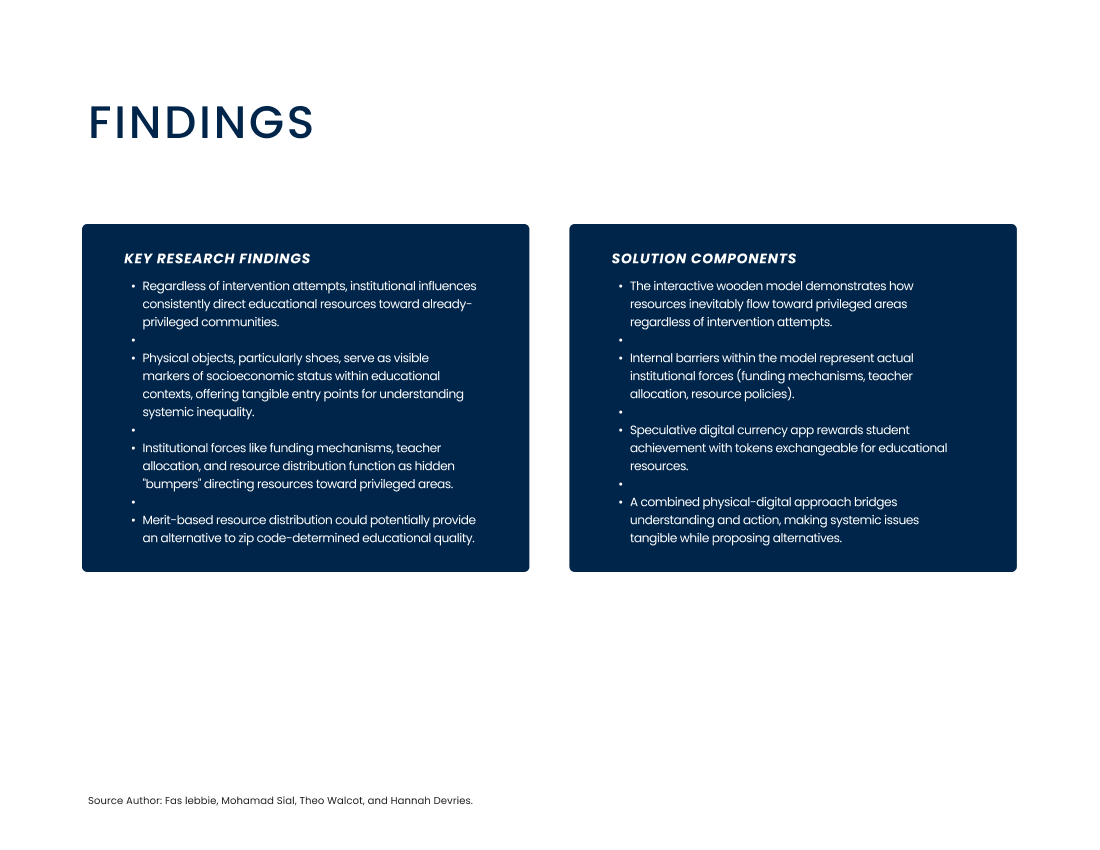

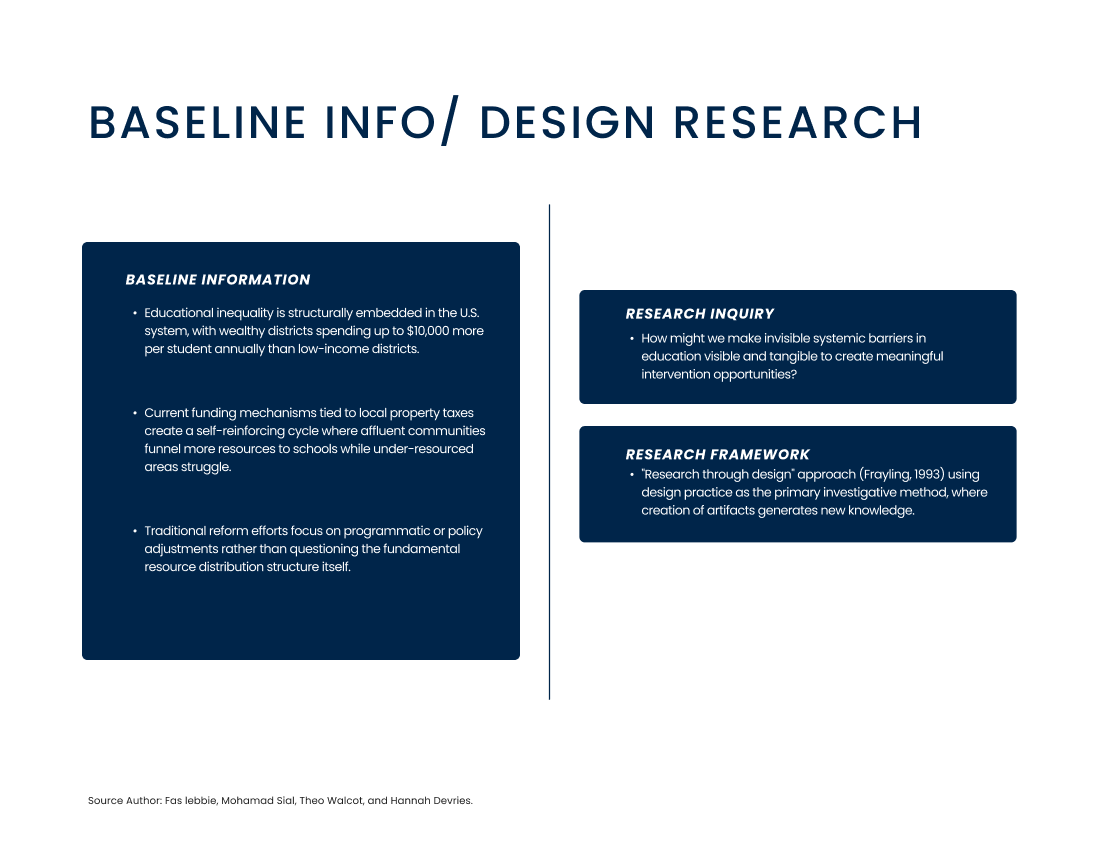

The American education system faces an equity crisis that is largely invisible. Around 53 million students navigate a system where educational quality depends on zip code, not merit. The funding structure, reliant on local property taxes, perpetuates a cycle where affluent communities funnel more resources to their schools while under-resourced areas struggle with inadequate funding and support. This inequality is evident: wealthy districts spend up to $10,000 more per student annually than low-income districts. Students in underprivileged areas face challenges like fewer experienced teachers (with 31% higher turnover), outdated materials, limited technology access, and fewer extracurriculars. Disparities extend beyond the classroom—children in low-income households may receive less homework help, face food insecurity, or need to contribute financially, impacting their education. Traditional reforms focus on programs or policy tweaks rather than questioning the resource distribution structure. Accepting the current funding mechanism limits imagining equitable alternatives. Systemic barriers are embedded in policies and practices, making them hard to address. Our research found a gap in communicating educational inequality: the abstract nature makes it hard for stakeholders to grasp, limiting public understanding to statistics rather than structural comprehension.