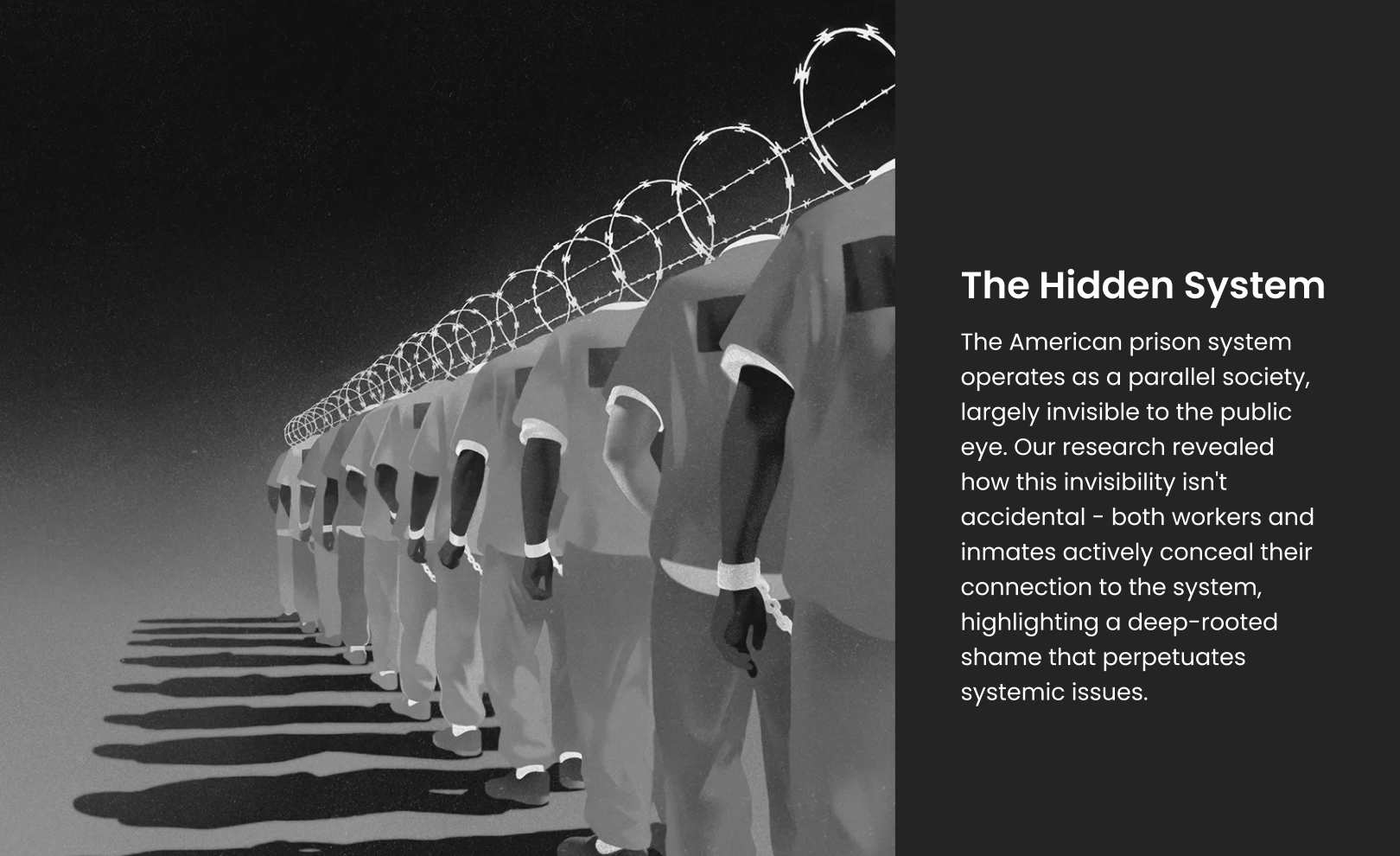

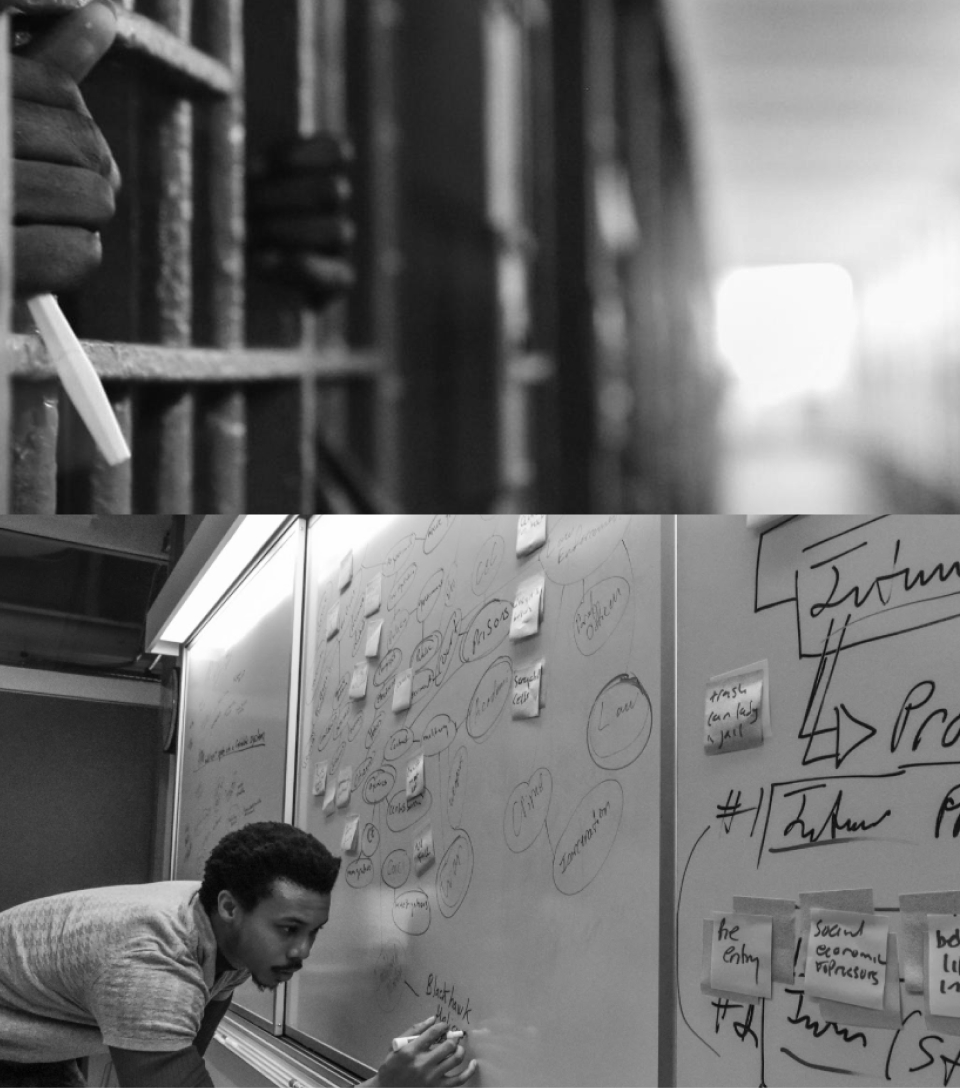

At the beginning of this research, we faced significant challenges in recruiting interview subjects due to stigma and privacy concerns. One trusted inmate represented us and gave us access to his circle of trusted participants. This required adapting our methodology, offering anonymity and alternative interview formats to gain trust and access valuable perspectives. Our ethnographic approach involved comprehensive methods to understand the corrections system better. We conducted in-depth interviews with former inmates, correctional officers, and family members to gather varied perspectives on prison experiences. We utilized systems mapping exercises to visualize complex dynamics, while journey mapping analyzed intake and release processes in detail. To enrich our findings, we conducted a documentation analysis of prison procedures and policies and a language analysis to explore how terminology shapes incarceration and rehabilitation perceptions. Our research approach combined elements of all three of Frayling’s research categories. However, it was primarily anchored in “research through design,” as we used design methodologies to generate new knowledge about the incarceration system.

Research “FOR” Design

We began with extensive documentary analysis, studying films like “Prison in 12 Landscapes” and “13th Amendment” to establish context and understand historical patterns. This preliminary research allowed us to enter the field with informed perspectives and identify key areas for investigation. Statistical analysis of incarceration rates and demographic patterns provided a quantitative foundation for our qualitative exploration. This research served our design process by identifying where to focus our attention and which stakeholders to engage.

Research “THROUGH” Design

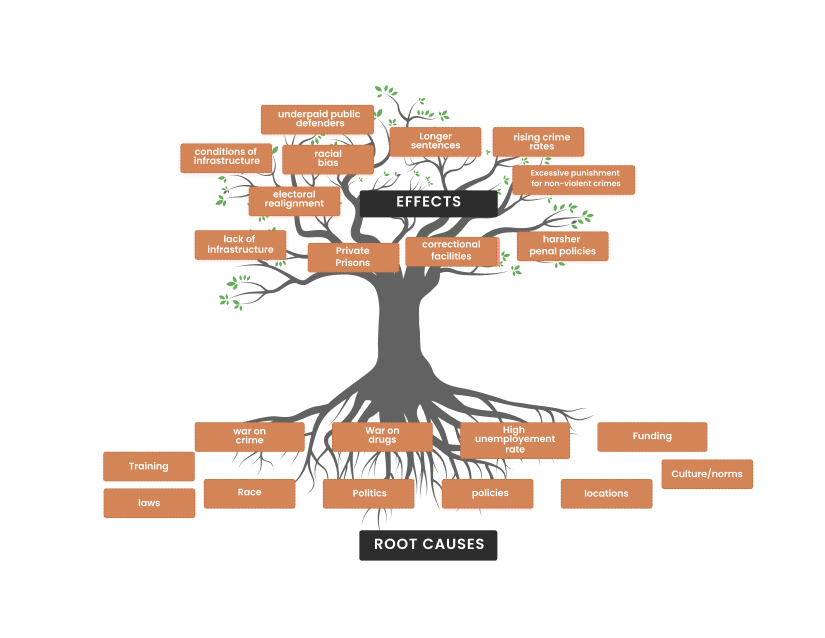

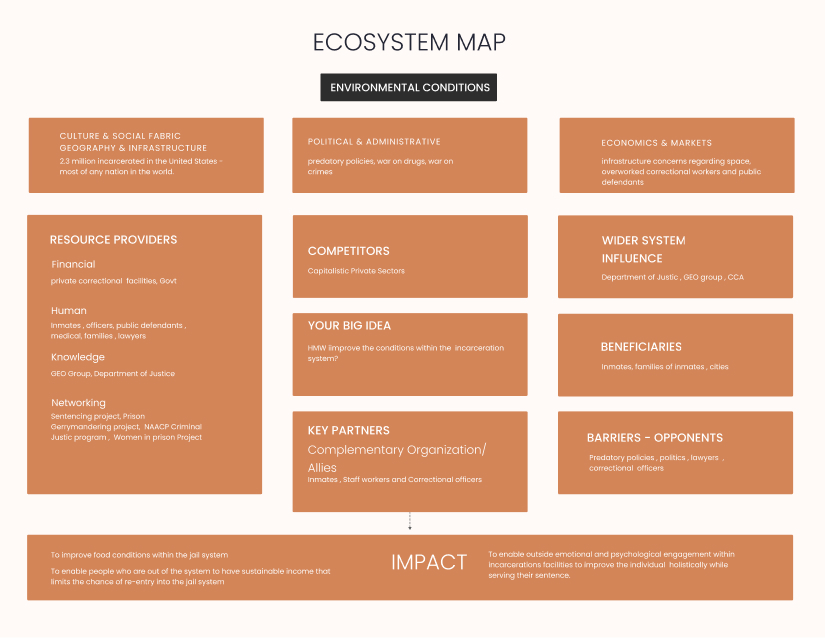

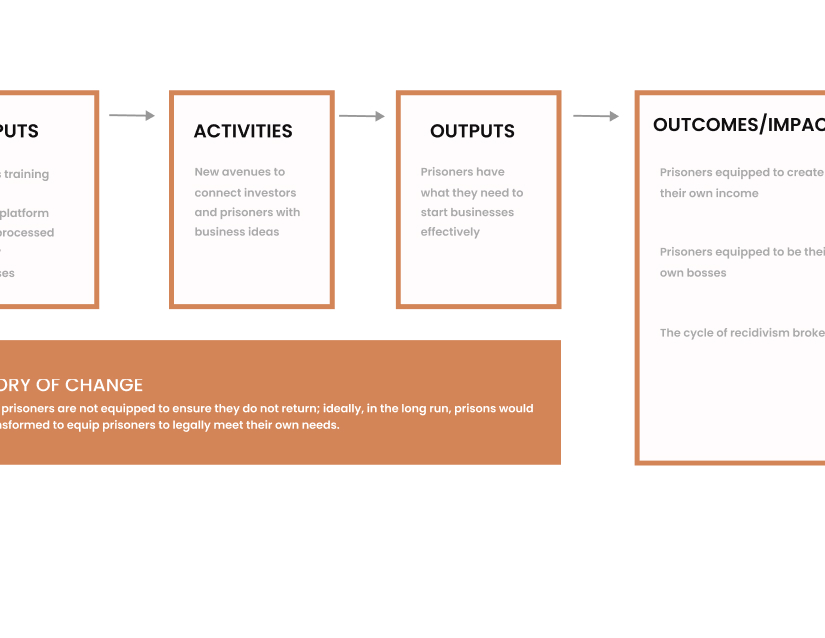

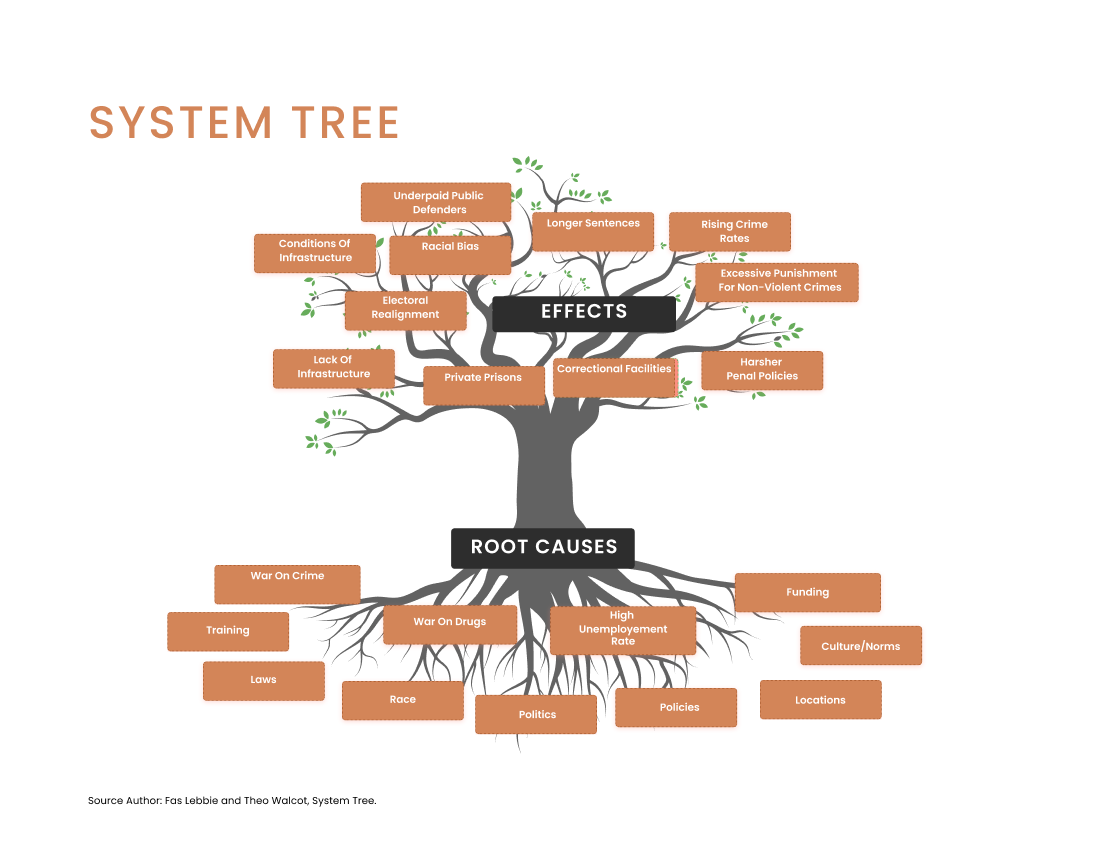

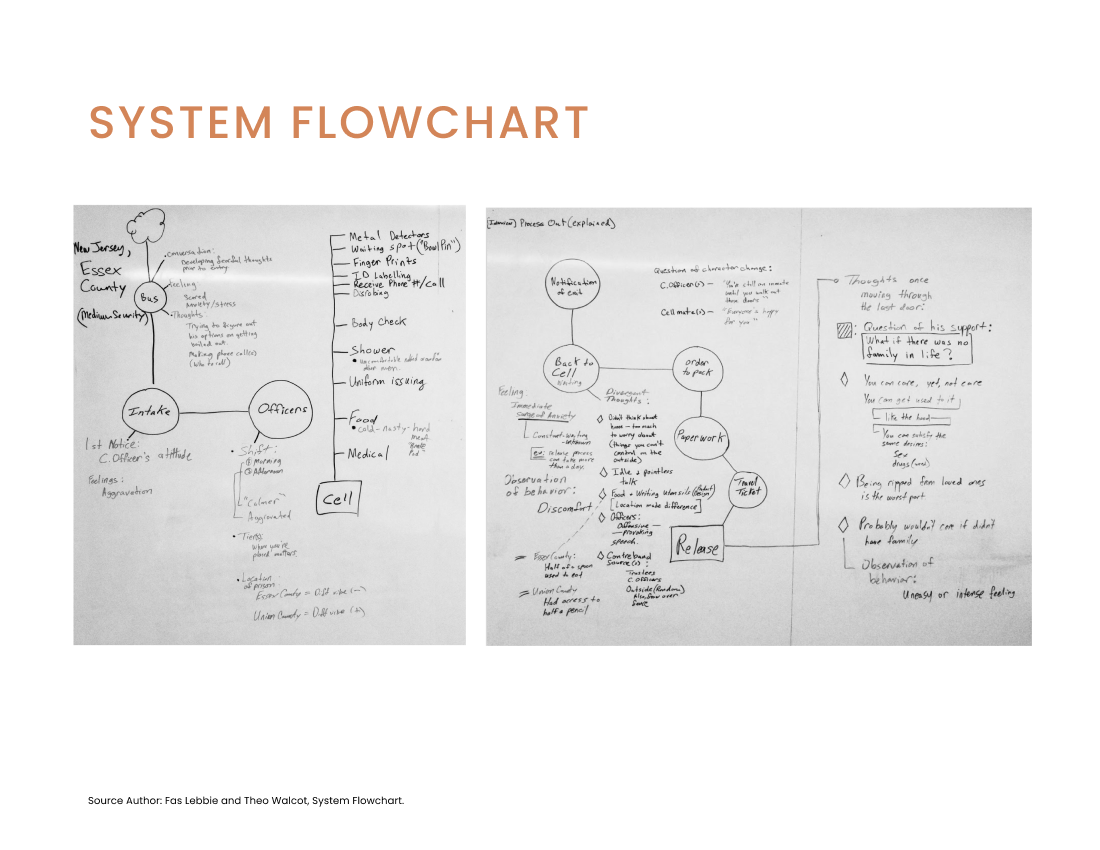

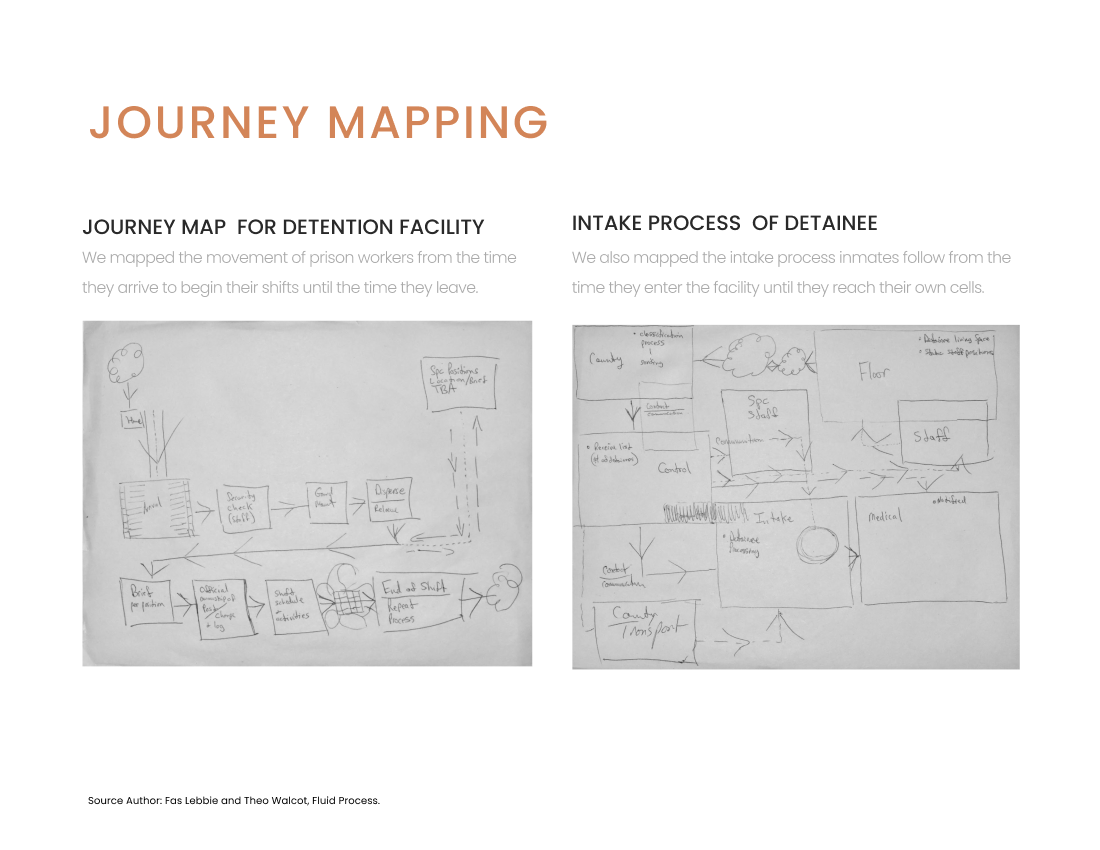

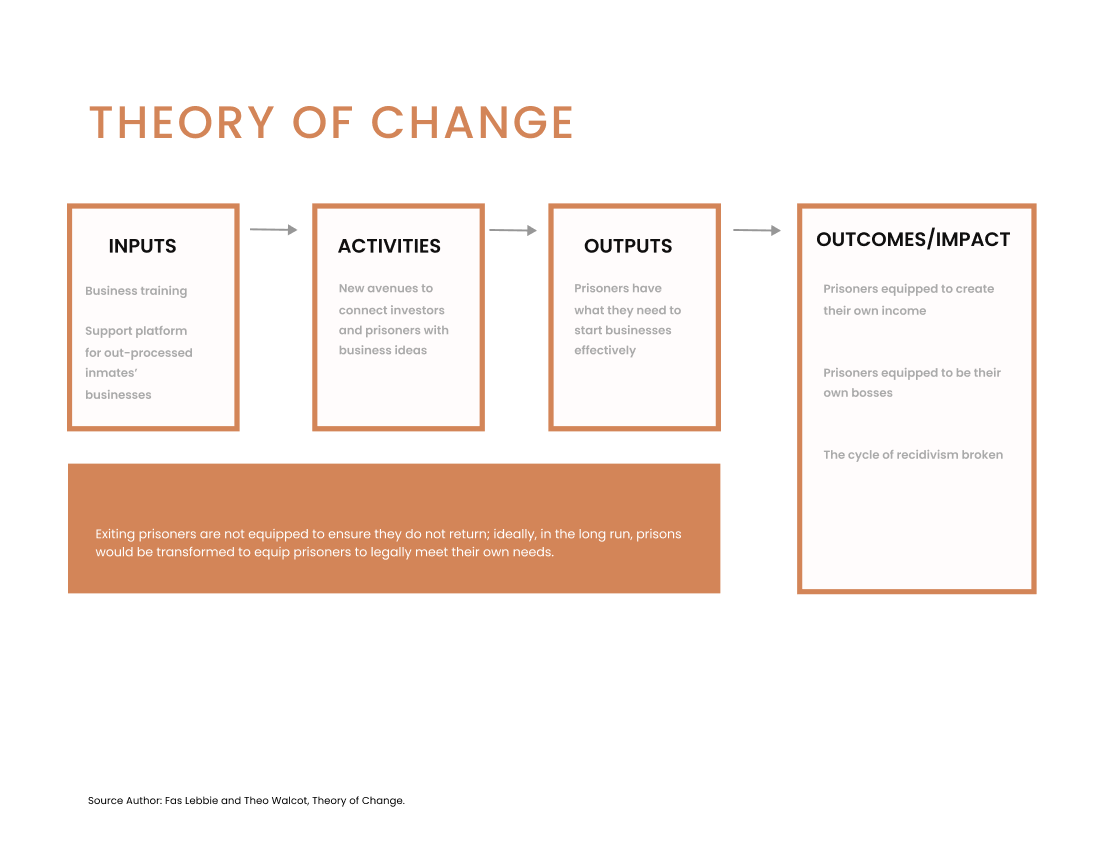

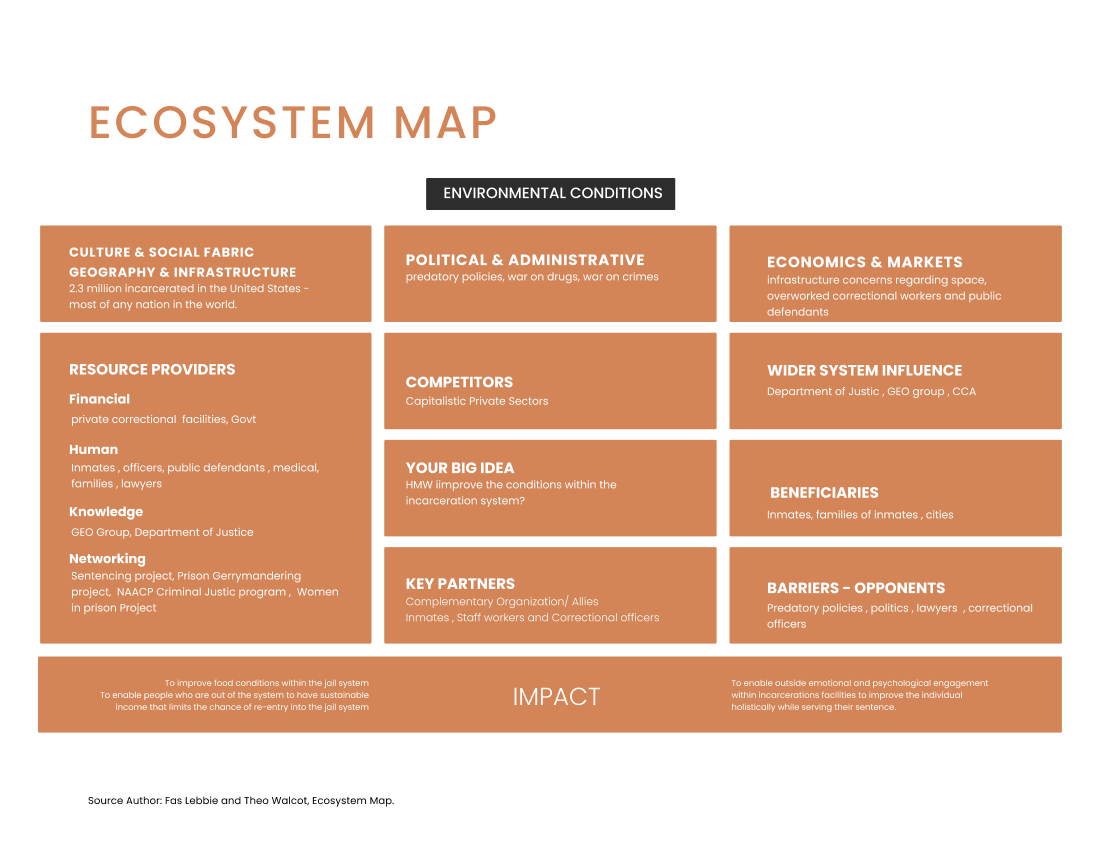

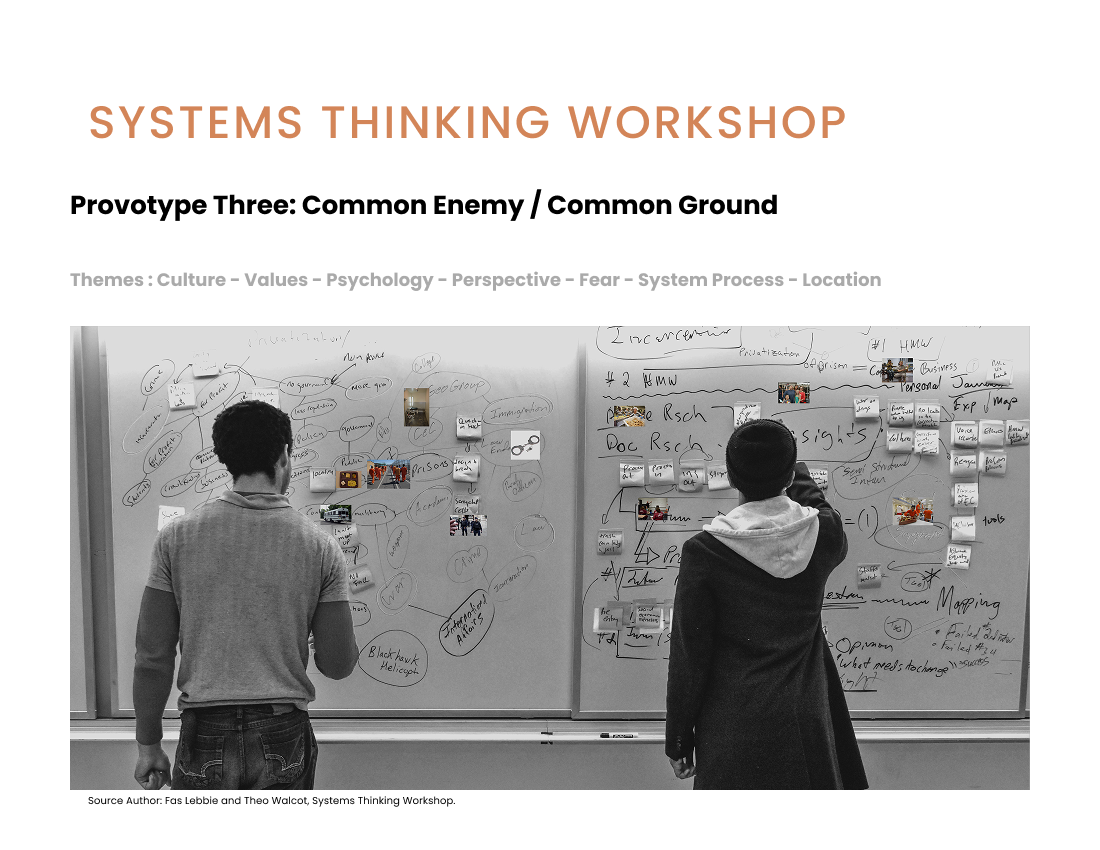

The core of our approach involved using design methodologies as investigative tools to generate new knowledge. Through systems mapping, journey visualization, and iterative diagramming, we uncovered insights that would have remained hidden through traditional research methods alone.

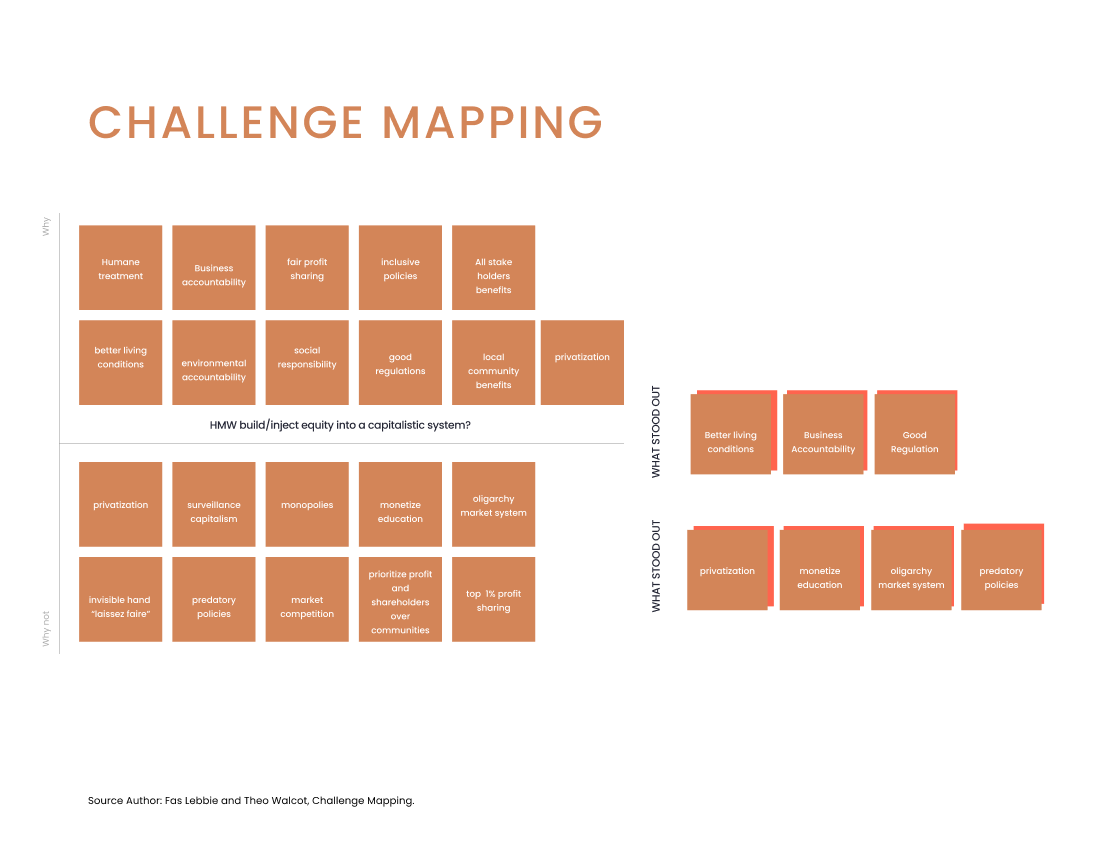

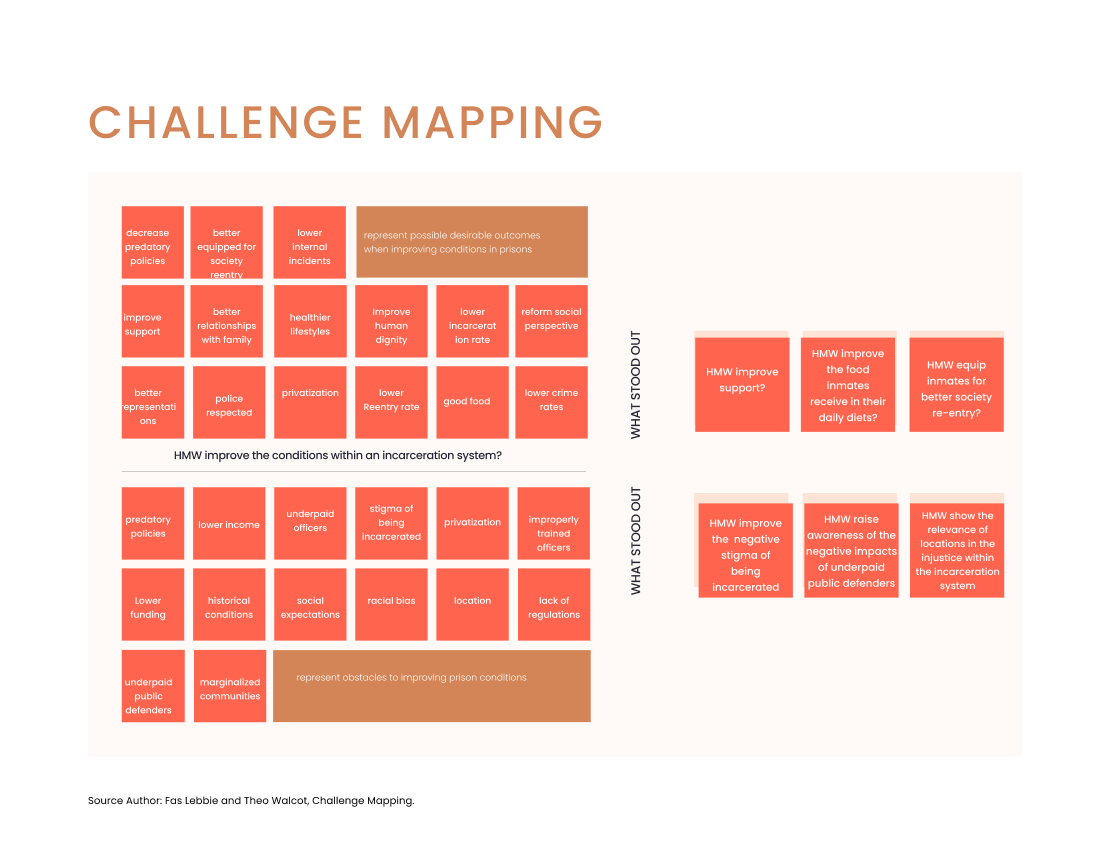

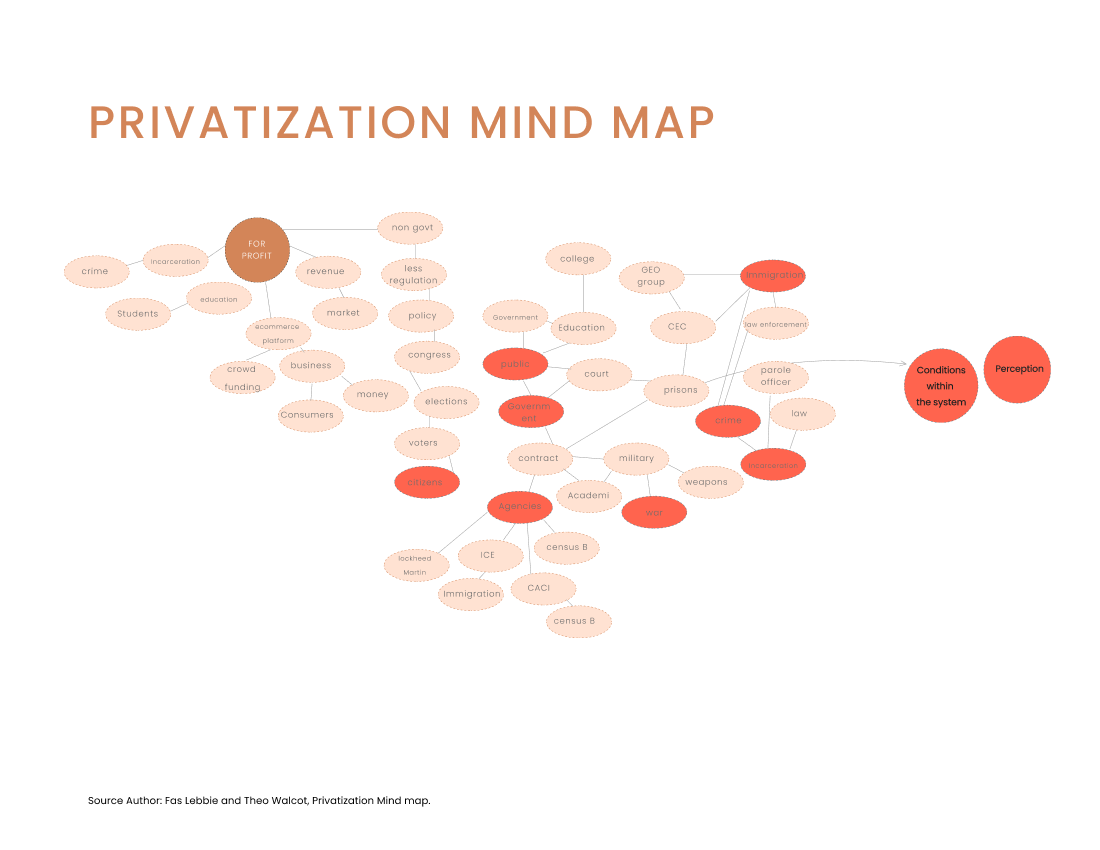

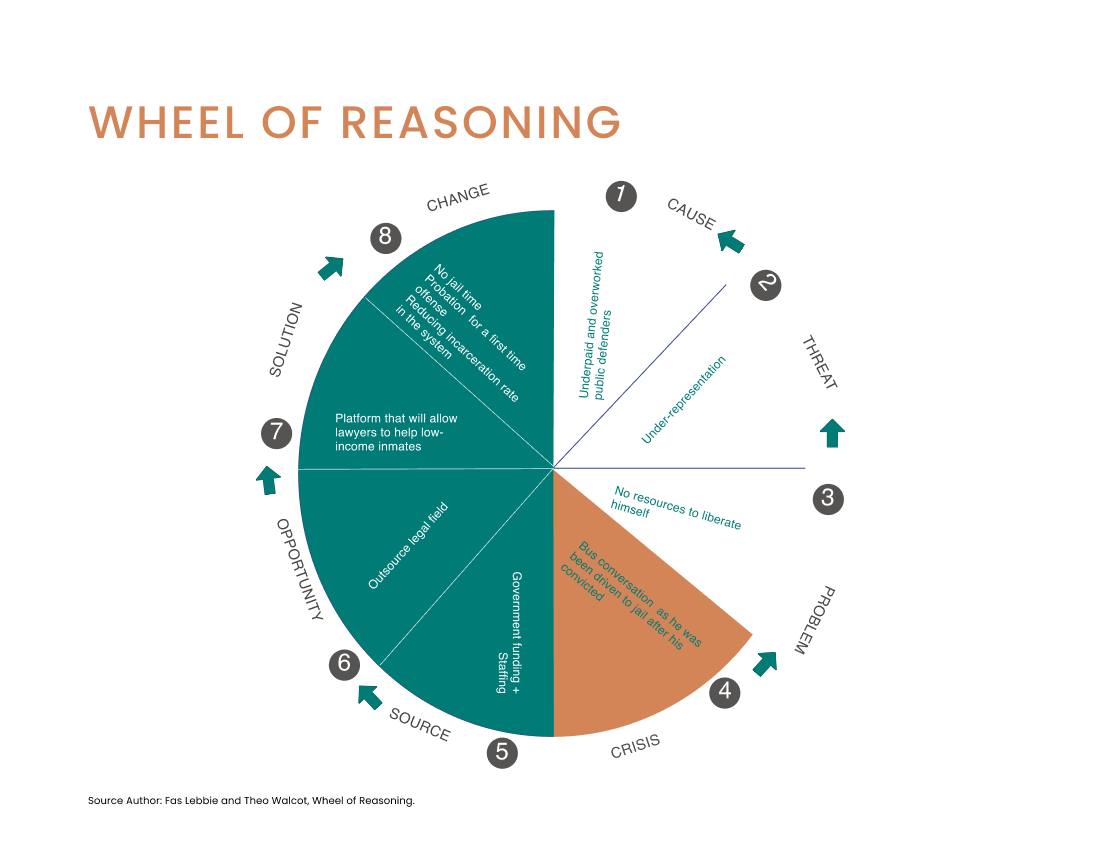

Our “Challenge Mapping” exercises improved our understanding of how privatization influences the system, revealing its dual nature as both an opportunity and an obstacle. Through multiple iterations, we refined our research questions, moving from general inquiries about capitalism to specific questions about improving conditions within the system.

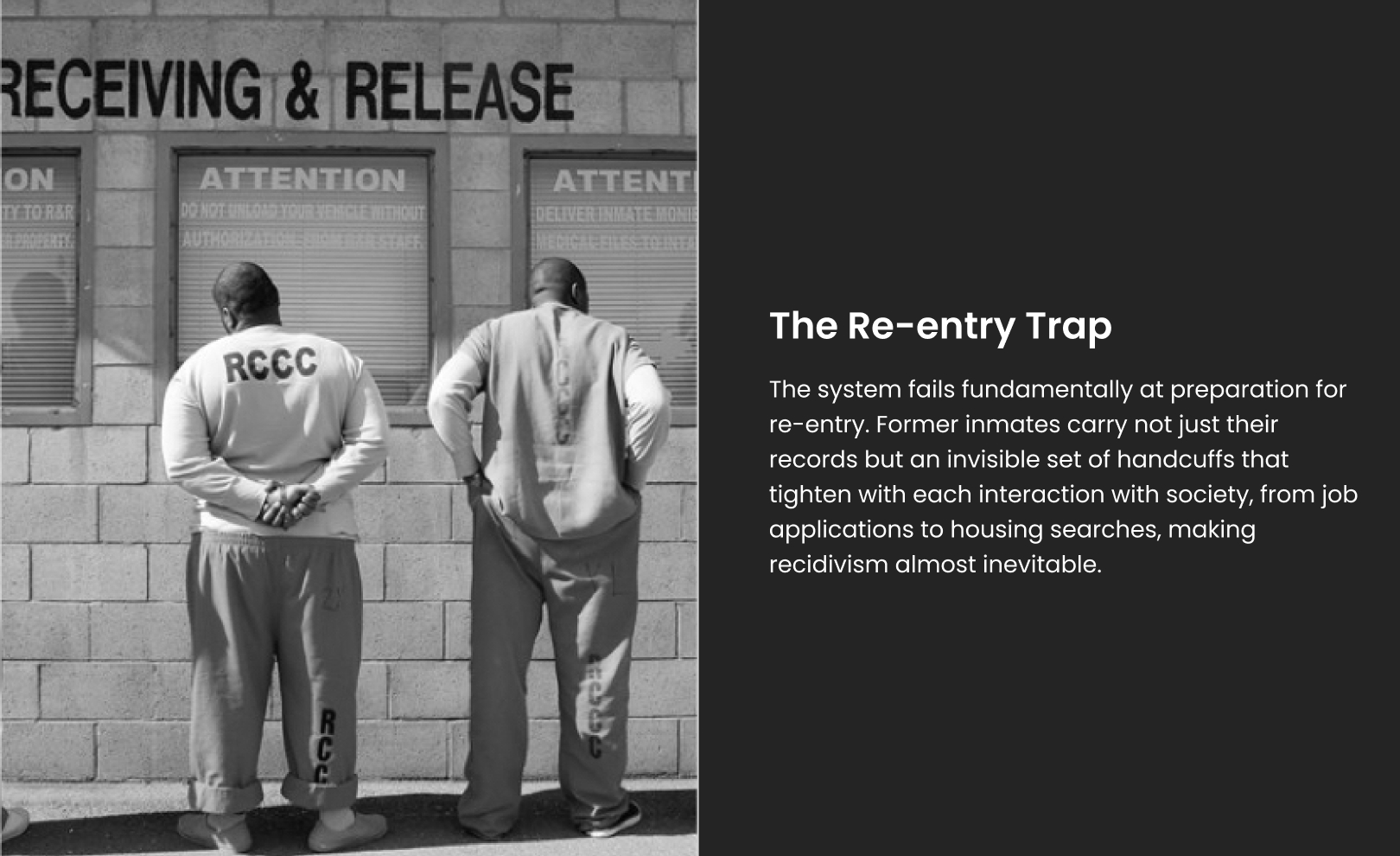

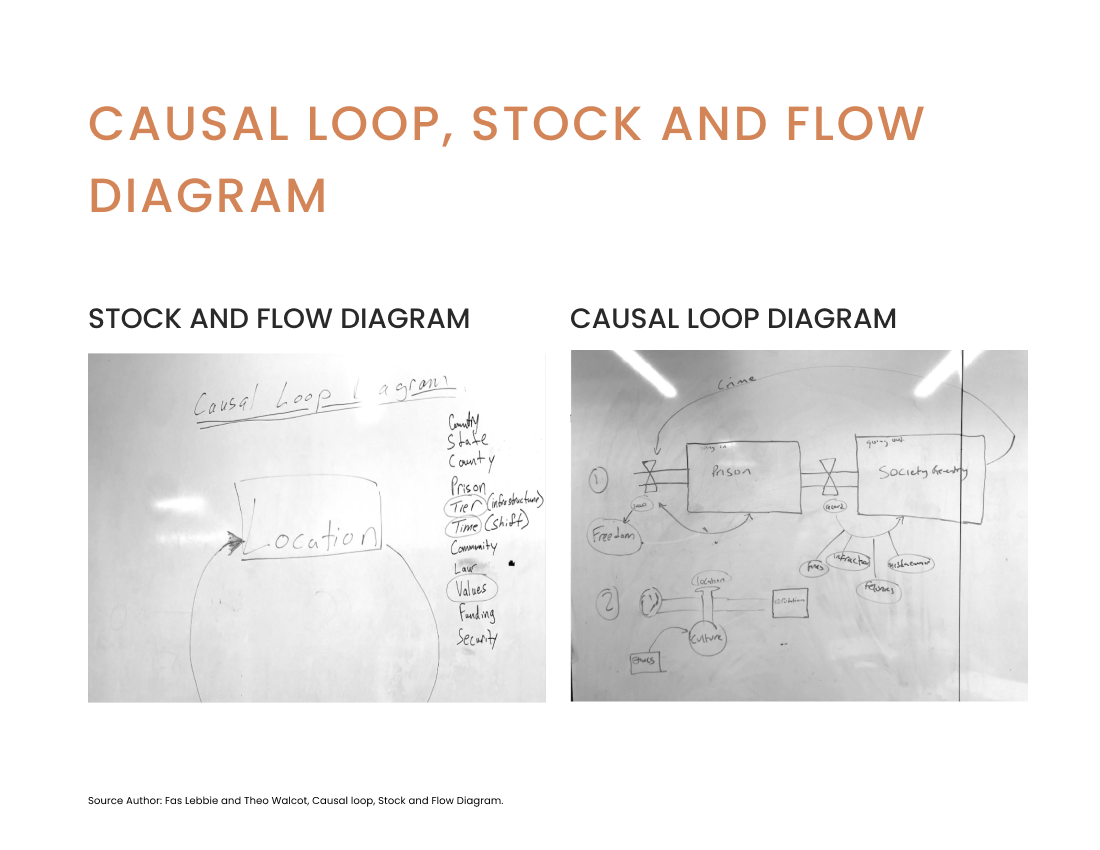

The creation of Stock and Flow diagrams allowed us to visualize prisoner movement through the system, uncovering the cyclical nature of incarceration and the factors that lead to recidivism.

Research “INTO” Design

We analyzed how the design of prison environments and processes shapes the human experience. Our investigation of the “Choreography of Handcuffs” examined how physical restraints serve as both practical tools and powerful symbols within the system, reflecting broader power dynamics. By studying intake processes, facility layouts, and release procedures, we gained insights into how intentional and unintentional design decisions impact those within the system. This analysis of design precedents and their effects contributed to our understanding of what would and wouldn’t work in future interventions.